Discovery is where most civil cases live or die. It’s the formal process for parties to exchange information, documents, and testimony before trial — but it’s also where disputes, delay tactics, and huge bills are born. Below is a practical, lawyer-friendly primer you can use as a blog post or client explainer: what discovery is for, why it’s expensive, how it’s weaponized, what the answering party must do, and what happens if you screw it up.

What discovery is — and why it exists

Discovery is the set of procedures (interrogatories, requests for production, requests for admission, depositions, subpoenas, and electronic discovery) that lets parties obtain the facts, documents, and expert information necessary to prepare for trial or settlement.

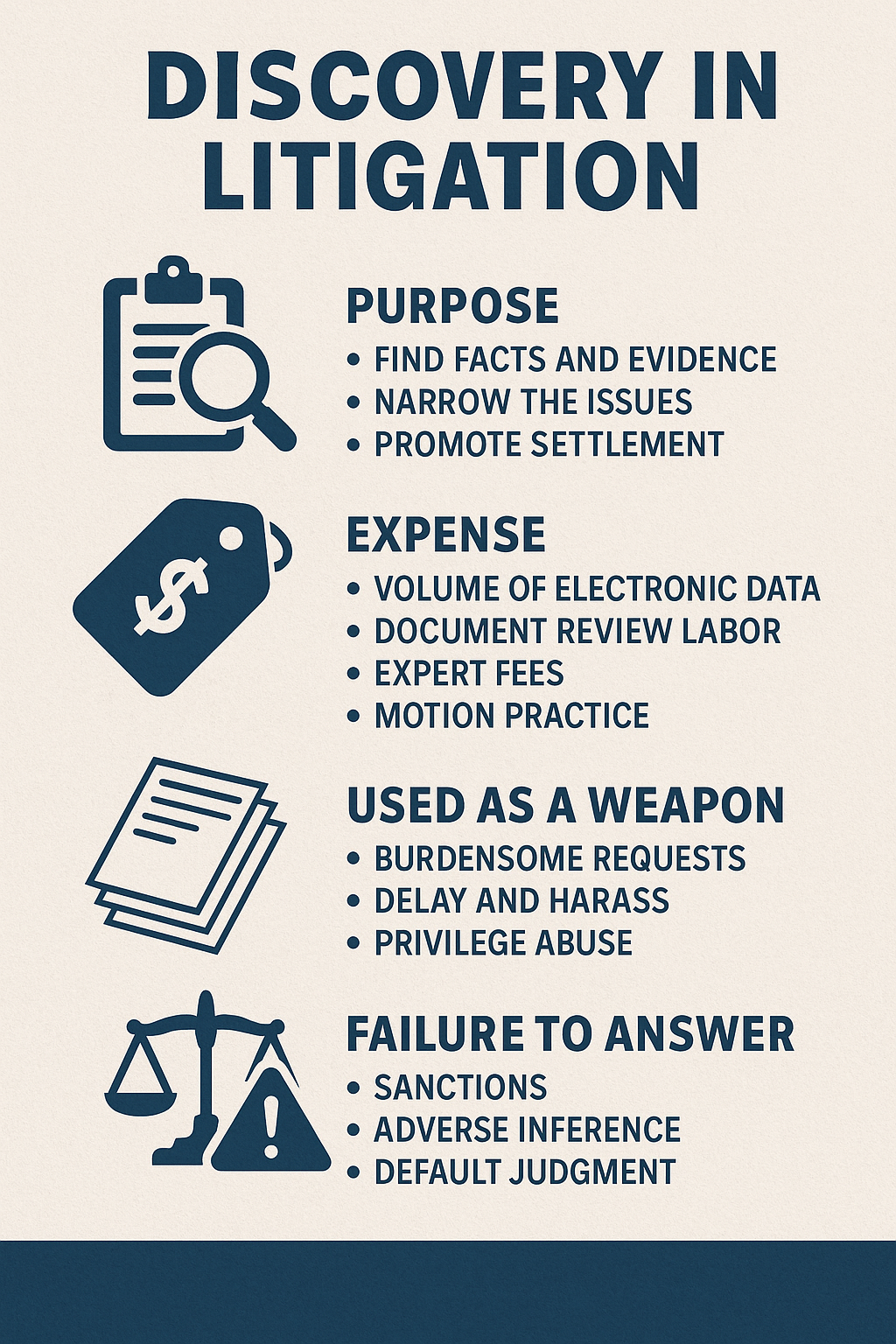

Purpose:

- Fact-finding: reveal what each side knows and what evidence exists.

- Narrow the issues: clarify disputes and narrow contested facts.

- Preserve testimony and evidence: depositions lock in witness recollections, document requests preserve documentary evidence.

- Promote settlement: with fewer surprises at trial, parties are more likely to evaluate realistic outcomes.

- Prevent ambush: both sides must disclose key items; trial should be about contesting facts, not hiding them.

The common discovery tools (short)

- Interrogatories: written questions answered under oath.

- Requests for Production (RFPs): asks for documents, ESI, photos, contracts, etc.

- Requests for Admission: ask the other side to admit/dispute facts or authenticity.

- Depositions: sworn oral testimony under oath, often with exhibits.

- Subpoenas: used to collect documents/testimony from non-parties.

- ESI discovery: collection and review of email, metadata, servers, cloud data, devices.

Why discovery gets so expensive

There are several interacting reasons discovery often becomes the largest line item in litigation budgets:

- Volume of ESI (electronic data): emails, text messages, shared drives, Slack, cloud apps, backups, phones. Collecting, processing, hosting, and searching large datasets costs money.

- Forensic collection and preservation: proper ESI collection may require e-discovery vendors or forensic experts (to avoid spoliation claims).

- Document review labor: reviewing documents for relevance, privilege, and responsiveness is time-consuming and often billed by the hour or via vendor review platforms (linear review, reviewers, privilege tagging).

- Privilege and redaction work: identifying privileged material and preparing redactions requires careful, often attorney-level work.

- Meet-and-confer and motion practice: discovery fights (motions to compel, protective orders, sanctions motions) add depositions, briefing, and hearings.

- Experts: many disputes need expert discovery (forensic accountants, engineers, IT consultants) who charge high hourly and report fees.

- Costs of production: printing, uploading to platforms, producing native files, exporting metadata, and shipping exhibits incur vendor fees.

- Strategic complexity: more complex cases mean more tailored discovery (third-party subpoenas, international data, privilege logs) — complexity equals cost.

In short: data plus people plus legal time = money.

How discovery is used as a weapon

Discovery is neutral in theory but can be aggressively used to gain advantage:

- Volume overload (flooding): serve broad RFPs and massive requests to force the opponent into costly review and production.

- Fishing expeditions: overly broad requests hoping something useful turns up.

- Delay and attrition: drag out meet-and-confer, produce slowly, or bury key documents late to impair trial prep.

- Targeted harassment: serve intrusive or embarrassing requests to pressure settlement.

- Privilege games: over-assert privilege or use privilege logs strategically to obscure documents.

- Third-party pressure: subpoena customers, vendors, or banks to raise costs and friction.

- Weaponized motion practice: use repeated motions to compel or discovery motions to burden opposite counsel and client.

- “Sneak” evidence: use surprises (late document dumps or unexpected witnesses) to gain tactical advantage if disclosure rules are lax or the opponent didn't preserve.

Courts and rules aim to moderate this, but tactical abuse still happens — and litigators must anticipate and respond.

What’s required of the party answering discovery

The responding party has duties both substantive and procedural. Failing these duties has real consequences.

Key obligations:

- Preserve evidence (duty to preserve / litigation hold): once litigation is reasonably anticipated, you must preserve relevant documents and ESI. Failure = spoliation risk.

- Timely responses: respond by the rules’ deadline (often 30 days federal; state deadlines vary). Responses must be timely or accompanied by agreed extensions.

- Adequate, non-evasive answers: answers must be responsive and not evasive. Providing “we’ll produce later” without a plan can be risky.

- Proper objections and specificity: lodge timely, specific objections (e.g., overbroad, unduly burdensome, privileged) — boilerplate objections are weak. If you object, you often must state the grounds and, where possible, provide limit/scope.

- Privilege log: when withholding documents as privileged, provide a privilege log that gives enough information for the court and the other side to evaluate the claim without revealing privileged content.

- Supplementation duty: federal and many state rules require supplemental disclosures if you find new, responsive information.

- Reasonable search and production: a good-faith, reasonably tailored search for ESI and documents (not just a token search).

- Meet-and-confer in good faith: engage with opposing counsel to narrow disputes and avoid motion practice.

- Authentication and form of production: produce in agreed formats (native for spreadsheets, load files for ESI, OCR'd PDFs, and include metadata when required).

- Cooperate with discovery protocols: e.g., defensible deletion policies, agreed search terms, phased discovery, or clawback/protection orders.

Practical point for clients: discovery is not just a job for the lawyer — it requires client cooperation (locating custodians, devices, passwords, and answering questions truthfully under oath).

What can happen if discovery is mishandled or late

Consequences range from procedural inconvenience to case-ending sanctions:

- Motion to compel: court can order supplementation and award the moving party fees and costs.

- Expense shifting: losing party may be ordered to pay the other side’s discovery costs.

- Adverse inference instruction: if the court finds intentional spoliation, a jury instruction that evidence would have been unfavorable may be given.

- Striking pleadings or evidence: the court can strike affirmative defenses, pleadings, or exhibits for severe breaches.

- Default judgment or dismissal: in extreme cases, failure to comply can lead to default judgment or dismissal of claims/defenses.

- Monetary sanctions and attorney’s fees: fines, cost awards, and attorney-fee sanctions are common remedies.

- Criminal contempt (rare): in willful or repeated contempt situations, criminal contempt can be pursued.

- Reputational damage: discovery abuse can influence a judge’s view at trial and affect settlement leverage.

- Loss of ability to use evidence: untimely disclosure may result in exclusion of that evidence at trial.

Bottom line: treating discovery casually risks far more than an inconvenience.

Practical checklist for responding parties (actionable)

Use this checklist early and repeat it whenever new discovery arrives:

- Immediately trigger a litigation hold identifying custodians, devices, cloud accounts, and preservation steps.

- Identify custodians & sources (emails, phones, shared drives, cloud apps, backups).

- Inventory likely responsive categories (contracts, invoices, communications, photos, drafts).

- Assign roles & deadlines (who collects, who reviews, vendor if needed).

- Run reasonable searches (keyword lists, date ranges, custodians) and document your process.

- Review for responsiveness & privilege and prepare a privilege log for withheld items.

- Produce in agreed formats with required metadata and load files; include a production cover letter.

- Meet-and-confer early to narrow disputes, propose search terms or sampling, and consider proportionality.

- Address ESI disputes proactively — negotiate scope, phased production, and protective orders.

- Prepare witnesses for depositions; make sure client knows to not delete messages and to preserve chat threads.

- Supplement if new responsive information surfaces.

- Keep contemporaneous notes of collection, searches, and production steps (useful if spoliation allegations arise).

Tips to control cost and limit abuse

- Negotiate proportional discovery early: invoke proportionality (burden vs. benefit) to narrow scope of ESI collection.

- Use sampling and targeted searches: propose small, custodian-limited searches and iterative productions rather than “give me everything.”

- Agree on search terms and custodians: joint protocols cut disputes and vendor fees.

- Use technology wisely: analytics, deduplication, and predictive coding can lower reviewer hours.

- Insist on protective orders: limit scope and sharing of sensitive information; facilitate clawback agreements for privilege mistakes.

- Stipulate production formats up front: avoid costly reprocessing later.

- Work with your client early: centralized document gathering and client-guided searches reduce missed documents and re-review.

- Explore mediation/early neutral evaluation: early resolution can eliminate costly discovery battles.

Short sample timeline (typical civil case)

- Days 0–14 after filing: issue litigation hold; identify custodians.

- Days 14–60: initial disclosures; serve/receive first discovery (interrogatories, RFPs).

- Days 30–90: collect & process ESI; run searches; begin review.

- Days 60–120: produce documents; meet-and-confer to resolve disputes and narrow scope.

- Days 90–180: depositions and expert discovery; supplement productions as needed.

- Ongoing: respond to additional discovery, handle motions to compel, and prepare exhibits for trial.

Exact deadlines depend on rules and scheduling orders — plan early.

Client-facing advice (what to tell your client)

- Do not delete anything once litigation is likely. Preserve under penalty of sanctions.

- Be honest with your counsel — hiding facts makes things worse.

- Expect discovery to take time and cost money; early cooperation reduces both.

- Search personal devices and private messages if they’re relevant — they’re discoverable if relevant.

- Keep clear records of who searched what and why.

Conclusion — discovery is a legal and strategic art

Discovery is where legal strategy meets project management. Done well, it produces the facts you need, helps you win or reach a sensible settlement, and protects you at trial. Done poorly—or weaponized by an adversary—it’s a costly, risky minefield. Good lawyers blend legal acumen with disciplined processes, early client cooperation, and smart use of technology to keep discovery focused, defensible, and cost-effective.

At David C. Barsalou, Attorney at Law, PLLC, we help clients navigate business, family, tax, estate planning, and real estate matters ranging from document drafting to litigation with clarity and confidence. If you’d like guidance on your situation, schedule a consultation today. Call us at (713) 397-4678, email barsalou.law@gmail.com, or reach us through our Contact Page. We’re here to help you take the next step.